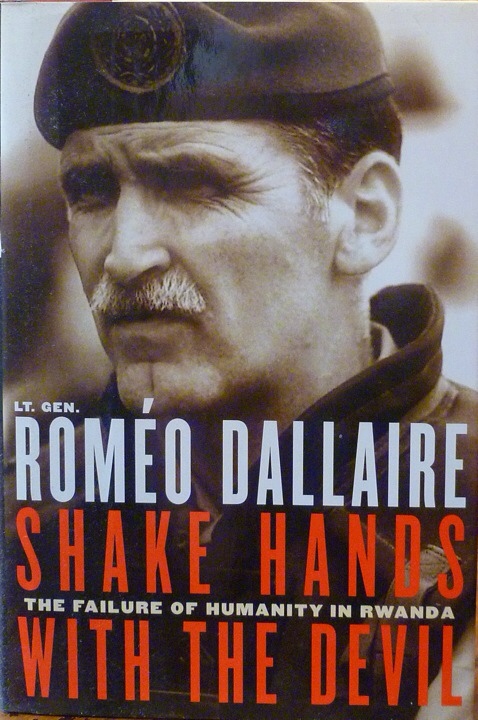

Naked Imperfection was my #FridayReads last weekend, and it gripped me straight through until early this week. Gill Deacon is the host of CBC Radio’s daily afternoon show from Toronto, Here and Now, with a voice that’s good company on the air, and which translates well in print. Prior to her broadcasting career, she was an environmental journalist and consumer health advocate. She lived consciously and consumed carefully, avoiding products that could harm her, her family, and her fellow denizens of the earth. She wrote an earlier book called There’s Lead in Your Lipstick. This made her all the more ill-prepared when she received a chilling diagnosis of breast cancer. She propels her narrative forward rapidly, in modified stream-of-consciousness style, with many of her paragraphs built of staccato sentences, like this one, after she’s had a mastectomy: “Tonight, as Grant and I move between the sheets in the blue-grey, pixelated, late-night bedroom light, I look down at my chest. A single orb of flesh presses up against my husband’s chest, its twin felled—an abandoned goddess, carrying on alone. Beside it, the graveyard of ribs. I am snatched by the escapist pleasure of my husband’s touch by the reminder of what had happened. Mourning the imperfect body I once had. I wish I still had two breasts. Sometimes the sadness surfaces like a beluga gasping for air. How can I be grateful for being misshapen.” The closing chapters were so well-crafted, I slowed my reading, lest I finish the book too quickly. I kept paging back to re-read passages I’d just read, so apt were they about living a full life, even if an imperfect one. After writing candidly about the prosthetic breast she got after her surgery, Deacon ends her book, some years in to the slow-motion crisis, with good news from her doctor, who “used the words cancer and gone in the same sentence. ‘Go out and live your life,’ she said with a smile. ‘You’re always going to have more doctor’s appointments than most of your friends, and technically it takes more than five years before the odds of you getting cancer drop down to match the general population, but for all intents and purposes your cancer is gone. Get back to whatever you were doing before this disease rang your bell.'”

Much of my recent reading and other cultural consumption has featured people who through accident or illness have endured the loss of parts of themselves, like Miles O’Brien, whom I tweeted about above. To his credit, he not only wrote in New York magazine about the frightening accident—when on a reporting trip to the Philippines last February he suffered an accident that led to the amputation of his left arm—he also reports on the neurological sources of phantom pain, and the design and engineering of high-tech prosthetics, a field that’s burgeoning due in part due to the return home of many wounded veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the growth of miniature electronics.

Relatedly, I later listened to a gripping episode of a new CBC radio series called Live Through This. It featured an account of Paul Templer, a wilderness guide in Zimbabwe who survived an attack by an aggressive hippo that nearly killed him, though he lost an arm in the melee, during which he was for some time in the gaping mouth of the animal. Templer healed and was fitted with a prosthetic arm. He later guided another trip down the Zambezi River, to raise money that will help victims of land mine explosions receive prosthetic devices of their own.

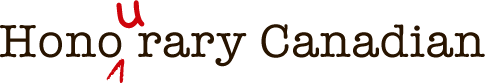

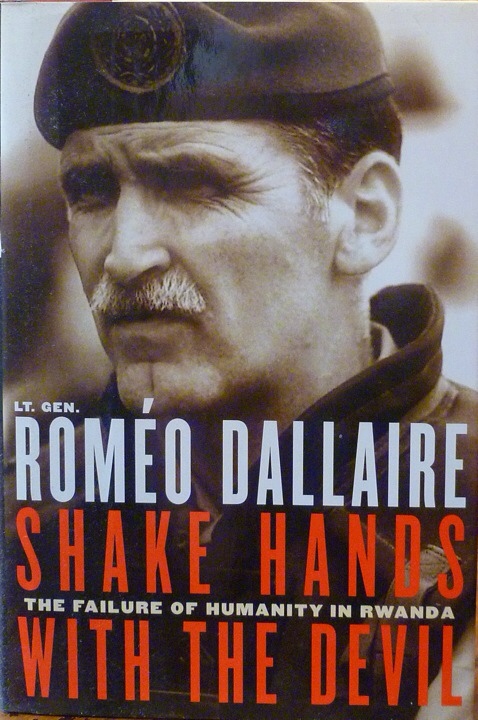

These incidents reminded me of what my longtime author Lt General Roméo Dallaire told me in 2006, when he was in New York City, promoting Carroll & Graf’s edition of his Canadian bestseller, Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. Reflecting on the PTSD he’s been afflicted with ever since, as commander of the under-manned UN Peacekeeping Force in Rwanda in 1993 he endured the searing experience of trying to prevent the genocide, he told me: “When I slip into depression, the medicines and therapy act like a prosthetic and keep me from falling.”

It occurs to me that in some ways human evolution is a long-running narrative of the development of various kinds of prostheses, from the first crutch to aid a hobbled walker, to the development of finely ground lenses for eyeglasses, the fitting of dental plates (the latter two are prostheses that I use every day), limbs, and other miscellaneous body parts. Even the wheel can be seen in this light as an aid to our daily work, and the club or hammer. Whether affixed and integral to our body; an extension of our hand or arm; or wholly apart from our person, it it fair to say that tools = prosthetics, and vice versa.

These were among the reflections stirred up in me while reading Gill Deacon’s astonishingly fine memoir, a superb first person narrative. I recommend it if you want to read a candid memoir, and if you, or a friend or relative, has been ill. There’s lots of hope and bright humor in this honest book.

N.B. Gill Deacon’s book is the second terrific memoir I’ve read by a female Canadian writer in the past few months, the earlier one having been Jan Wong’s Out of the Blue, which I made a #FridayReads last March 14 and wrote about again on March 21, after I’d finished it.