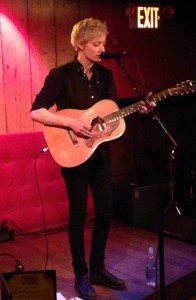

I recently heard a fascinating radio episode on the public radio program The World about a dialect of French heard nowadays exclusively in the regions of Canada where people of Acadian descent live today, Nova Scotia (NS) and New Brunswick (NB). It’s called Chiac, a name derived from a nearby town, Shediac, NB, that calls itself “Lobster Capitol of the World.” The program had run a shorter version of this half-hour podcast on WNYC, and I’m listening to the full version while writing this post. I was particularly excited when at the end of the radio bit they played a song by the incomparable Lisa Leblanc, who I heard live and loved at the CMJ festival in 2014, shown here.  As readers of this blog may recall, I’ve traveled a lot in Atlantic Canada, including through Acadian locales, including the scenic island of Cape Breton, NS, where I learned about the mass expulsion of 1755-1764 which the British Navy forced on French-speaking people who’d settled in the region. I’d never known the local dialect had a name.

As readers of this blog may recall, I’ve traveled a lot in Atlantic Canada, including through Acadian locales, including the scenic island of Cape Breton, NS, where I learned about the mass expulsion of 1755-1764 which the British Navy forced on French-speaking people who’d settled in the region. I’d never known the local dialect had a name.

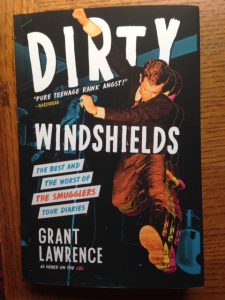

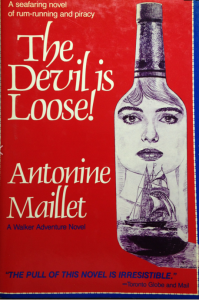

Relatedly, as editor at Walker & Co in 1987, I published the US edition of a novel by one of New Brunswick’s most honored writers, Antonine Maillet (b. 1929) of Bouctouche, NB, a town just north of Shediac facing the Gulf of St Lawrence across from the southern shores of Prince Edward Island. The book had come out in Canada a few years earlier, and I acquired US rights from a doyenne of Canadian publishing, Louise Dennys, for many years with Random House and Knopf Canada who was then part of her own company, Lester & Orpen Dennys. Maillet’s book was a fantastical historical novel, featuring a female pirate named Crache à Pic (translates as ‘spit-in-your-eye), skipper of a ship called Sea-Cow. who while Prohibition prevails in the States is running whiskey to American smugglers’ boats in the north Atlantic. My flap copy read, “Immediately reminiscent of Compton Mackenzie’s Whisky Galore and Howard Frank Mosher’s Disappearances, the Walker Adventure Series is pleased to publish The Devil is Loose! and Antonine Maillet, a storyteller of international reputation.”

Mackenzie’s 1947 novel was set during WWII, when a whisky-laden ship runs aground near the aptly-named Great Todday and Little Todday, Scottish islands whose ration of spirits has run out, leaving locals high and dry, who must decide what to do with the contraband; it was adapted for the funny movie, Tight Little Island. Mosher’s Disappearances is a multi-generational romp featuring a family who sometimes go by the surname Goodman, and sometimes Bonhomme. They live in the mythical Northeast Kingdom, Vermont’s northernmost region, and run liquor across the very real Lake Memphremagog, a long body of fresh water that straddles the border with Canada. I used to quote the opening paragraph for customers who I thought would enjoy the novel. Mosher has since written many novels set in Kingdom County.

Maillet was by 1987 already the author of more than 25 novels and plays, rich work that draws on a centuries-long store of folklore and local knowledge, about which she’s a scholar. In ’87, she traveled to NYC from Montreal, where she divides time with Bouctouche, and gave a talk at the Americas Society on Park Ave. Her tour in the US was subsidized by the cultural ministry of Quebec. I’ll add, from the year I entered publishing as an editor, in 1986, Canadian authors I published in the US, including Lt Romeo Dallaire and Margaret Atwood, often received significant support from federal and provincial agencies, eager to promote Canadian writers, including authors freshly launched in their careers, like Steven Galloway, whose first adult novel Ascension I brought in 2002. This held true until a few years in to the reign of PM Stephen Harper, whose government shut off the funds for cultural exchange to the US. I’m hopeful the cultural outreach will be restored and reinvigorated under PM Justin Trudeau.

Maillet is a mighty woman of rather short stature, and quite striking in appearance. We found that the lectern reserved for her was too tall, and unaccountably the venue had no stool or riser for her to stand on. Fortunately, I found a big box holding many reams of photocopy paper and at this ultra white-shoe venue she stood atop it to read from her novel, and lecture in a forceful, accented English about the French vernacular in which she wrote the book, and much of her work. Though I don’t think she called it Chiac, she described the local tongue, and its grounding in the French spoken by arrivals in the new world beginning in the 16th century. She likened it to speaking the French of Rabelais, who I note died in 1555! She described the settlers’ remoteness from French in Europe, as France advanced in to the industrial revolution, an isolation that set the local language, as if trapped in amber. Maillet has also created theater characters like La Sagouine, a wise old woman who tells audiences stories and imparts lore, using the local vernacular. I feel like the live theatre piece must form the heart of Chiac. Maillet’s accomplishments are truly a marvel to be celebrated. I first learned of her when as a bookseller with Undercover Books in Cleveland, when in 1979, with an earlier novel—Pélagie-la-Charrette, or Return to the Homeland, an epic account of the Acadian expulsion, a diaspora that scattered them to other parts of North America, including Louisiana, where the Acadiennes, become Cajuns—she became the only North American writer, male or female, to win France’s most prestigious book prize, the Prix Goncourt.

I was aware that people of Acadian descent still maintain a kind of linguistic flavor now rare in the modern world, but was delighted to learn so much more about it in this excellent half-hour of radio. I love language stuff like this, all the better when it’s about one of my favorite countries, and one of my favorite regions in that country! Below is some detail from the podcast’s web page, which you can listen to in full here.

I was aware that people of Acadian descent still maintain a kind of linguistic flavor now rare in the modern world, but was delighted to learn so much more about it in this excellent half-hour of radio. I love language stuff like this, all the better when it’s about one of my favorite countries, and one of my favorite regions in that country! Below is some detail from the podcast’s web page, which you can listen to in full here.