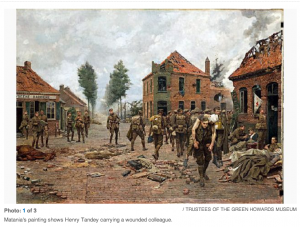

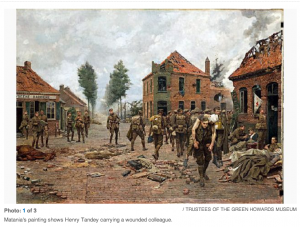

Kudos to the Toronto Star for running this story on a fascinating historical what-if that is examined in a new nonfiction book, The Man Who Didn’t Shoot Hitler: The Story of Henry Tandey VC and Adolf Hitler, 1918 by David Johnson. In a surprising twist, the mystery, a sort of urban legend about Hitler, is rooted in the painting shown here, depicting the aftermath of a battle in France, in 1914, early in WWI.

Kudos to the Toronto Star for running this story on a fascinating historical what-if that is examined in a new nonfiction book, The Man Who Didn’t Shoot Hitler: The Story of Henry Tandey VC and Adolf Hitler, 1918 by David Johnson. In a surprising twist, the mystery, a sort of urban legend about Hitler, is rooted in the painting shown here, depicting the aftermath of a battle in France, in 1914, early in WWI.

Star reporter Stephanie MacLellan writes that the oil painting—featuring the most-decorated British private, Henry Tandey, carrying a comrade on his shoulders—was commissioned in 1923 by Tandey’s regiment, the Green Howards, executed by war artist Fortunino Matania from a drawing made by a company draughtsman during a lull in fighting when a military hospital was being evacuated.

Many historians, including Tandey biographer Johnson, believe that Hitler was prone to embellishing his WWI record. For instance, his work as a runner, shuttling messages, was entirely behind friendly lines, not near hostilities. MacLellan picks up the tale in the 1930s, after Hitler had been elected to the office of German Chancellor:

“One of the German medical officers at First Ypres, [had been] a Dr. Schwend, [who] went on to join Hitler’s staff. According to Tandey biographer Johnson, Schwend stayed in touch with one of the British soldiers he treated, and in December 1936, the soldier sent him a copy of the Matania painting…. Hitler had his staff order a large photograph of the painting from the Green Howards. His aide sent a note thanking them for the artwork that captured a scene from Hitler’s first battle: ‘The Fuehrer is naturally very interested in things connected with his own war experiences. He was obviously moved when I showed him the picture. He has directed me to send you his best thanks for your friendly gift which is so rich in memories.’

“Hitler hung the photo in the study of his Bavarian retreat. It was here in September 1938, the story goes, that it was spotted by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who had come to Germany in his famed attempt to secure ‘peace in our time.’ According to [a] 1940 Canadian Press story, Chamberlain asked his host about this unusual artistic choice. ‘That man came so near to killing me that I thought I should never see Germany again,’ Hitler told him, pointing to Tandey. ‘Providence saved me from such devilish accurate fire as those English boys were aiming at us.’ On his return to England, Chamberlain telephoned Tandey at home to relay the story. To biographer Johnson, this is where the story starts to fall apart—starting with the fact that Tandey didn’t have a home telephone.”

The legend began with that inaccurate article in 1940, which according to MacLellan, left readers with the idea that, as Germans were routed from a battle at Marcoing, “one of them caught Tandey’s attention. He was quoted at the time, ‘I was going to pick him off, but he was wounded, and I didn’t like to shoot a wounded man,’ he said, according to the Canadian Press story that ran on the Toronto Star’s front page. Tandey didn’t know it at the time, he said, but the wounded German he had in his sights was Hitler, then a 29-year-old dispatch runner with the Bavarian army. It’s one of the most tantalizing what-ifs in history: What would have happened if Tandey had killed Hitler in World War I when he had the chance? The only problem, historians say, is that the incident probably never happened.”

“A more likely possibility, according to historian Thomas Weber [author of Hitler’s First War is that Hitler]— ever the embellisher—used the Tandey story to win political points with Chamberlain, who had come looking for assurances of peace. ‘I think it was just a good tool for Hitler to tell Chamberlain the story of an amicable Anglo-German encounter that he had….Hitler had an incredible talent to tell people he met exactly what they wanted to hear.’ And if he was going to have his life spared by a British soldier, who better than a famous war hero who had won a Victoria Cross, Military Medal and Distinguished Conduct Medal in a matter of weeks? In other words, Tandey.”

In addition, MacLellan reports that Hitler’s service records show that he couldn’t have been near Marcoing, where Tandey certainly was, on the dates in question. MacLellan and her sources fall squarely in the skeptical camp. Their reporting makes it seem remarkable that for the past several decades there have been people who believed a British soldier might’ve killed Adolf Hitler long before WWII, but declined to pull the trigger. For his part, in later years, Tandey doubted it happened at all.

Counter-factuals in historical reading are fun to make up and consider, but sometimes a purported counter-factual may just be non-factual. I think this example, probably more urban legend than anything else, points to our human impulse in which we wish we could erase terrible things from our memories and our common history. How much better the world would’ve been better off if Hitler hadn’t even been alive in the 1930s. To the mindset that believes in something like Henry Tandey’s lamentable decency at not finishing off a wounded enemy soldier, there is the accompanying, “But, he might’ve done it,” therefore keeping alive the hope it needn’t have occurred. This incident also reminds that errors and mis-reporting in news stories can have a knock-on effect lasting decades! I recommend you read Stephanie MacLellan’s whole article, one of the best reads in today’s papers.

To chronicle my recent Midwest August vacation, I’ve used Storify, the Web platform that lets bloggers incorporate social media posts in with their own writing. Once a piece is published on Storify, you can grab a handy embed code and paste it in at your websites, where it populates precisely as you’ve composed it. The piece is titled “By Train—STL to CHI/CHI to CLE/CLE to NYC, August 2014.” You may click here to read it at my page on Storify, or over at The Great Gray Bridge. I do hope you enjoy reading it, and if you also happen to enjoy writing sequential, diary-like narratives, I recommend you try Storify. It’s my second one, after “Great Music & Great Times in Toronto for NXNE, June 2014,” which includes travel and tourism info about Toronto, notes on restaurants, bookstores, shopping, and architecture, along with my music coverage of the NXNE festival, and which has now had more than 765 readers.

To chronicle my recent Midwest August vacation, I’ve used Storify, the Web platform that lets bloggers incorporate social media posts in with their own writing. Once a piece is published on Storify, you can grab a handy embed code and paste it in at your websites, where it populates precisely as you’ve composed it. The piece is titled “By Train—STL to CHI/CHI to CLE/CLE to NYC, August 2014.” You may click here to read it at my page on Storify, or over at The Great Gray Bridge. I do hope you enjoy reading it, and if you also happen to enjoy writing sequential, diary-like narratives, I recommend you try Storify. It’s my second one, after “Great Music & Great Times in Toronto for NXNE, June 2014,” which includes travel and tourism info about Toronto, notes on restaurants, bookstores, shopping, and architecture, along with my music coverage of the NXNE festival, and which has now had more than 765 readers.